Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (sometimes called chemo) uses drugs to kill fast-growing cells, like cancer cells. It is used to treat many types of cancer.

Goals of chemotherapy

You may be given chemotherapy with the goal of curing (eliminating) the cancer. Chemotherapy that is used to destroy cancer cells and increase the chances the cancer does not come back (recur) may be described as chemotherapy given with curative intent. If your healthcare team does not think that eliminating the cancer is possible, you may be given palliative chemotherapy. Chemotherapy given with palliative intent is used to relieve symptoms of advanced cancer, improve quality of life and help people with cancer live longer. Palliative chemotherapy may help shrink the cancer, keep it controlled (called stable disease) and prevent it from spreading to new places in the body. But it isn't given to cure the cancer.

Chemotherapy may be the only treatment you have or it may be used along with other cancer treatments, such as radiation therapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, or surgery. Chemotherapy may also be given in high doses as part of a stem cell transplant. You may have chemotherapy to:

- shrink a tumour to make it easier for surgeons to completely remove the tumour or to help radiation therapy reach cancer cells more effectively (called neoadjuvant therapy)

- destroy cancer cells left behind by surgery and reduce the risk that the cancer will come back (called adjuvant therapy)

-

relieve pain or pressure or manage other symptoms of

metastatic cancer -

treat cancer that has stopped responding to other treatments such as

radiation therapy orhormone therapy

How chemotherapy works

Chemotherapy uses drugs to destroy cells that grow and divide rapidly. Cancer cells grow and divide much more quickly than most normal cells in the body. This makes cancer cells good targets for chemotherapy. Cancer cells do not have the same ability as normal cells to repair themselves, which is why chemotherapy destroys them.

Some normal cells also grow and divide quickly, like those in the lining of the digestive system and hair follicles. Chemotherapy damages these normal cells along with the cancer cells. Damage to normal cells causes side effects, such as diarrhea, vomiting or hair loss. Since normal cells can usually repair the damage over time, these side effects tend to go away after you have finished chemotherapy.

With most types of chemotherapy, the drugs travel through the blood to reach and destroy cancer cells all over the body, including cells that may have broken away from the primary tumour. This is described as systemic therapy. Sometimes chemotherapy is used as a regional therapy for a specific area of the body. For example, high doses of liquid chemotherapy may be given directly into the bladder to treat bladder cancer.

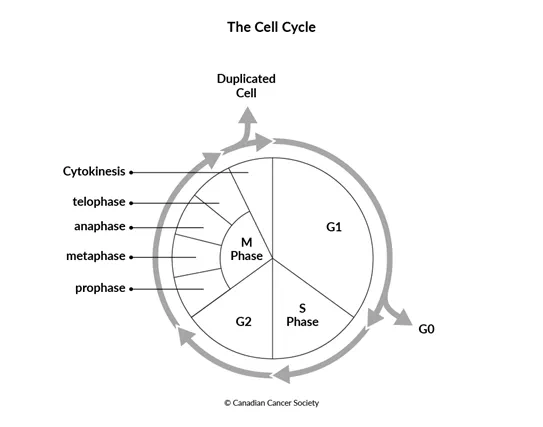

Chemotherapy drugs work by attacking cells during the cell cycle.

Cell-cycle nonspecific chemotherapy drugs attack cancer cells during any phase of the cell cycle.

Cell-cycle specific chemotherapy drugs attack cancer cells only during a certain phase in the cell cycle except for the G0, or resting, phase.

The cell cycle

The cell cycle is a series of steps called phases that normal cells in our body constantly go through to grow and divide.

Cells grow and divide more quickly when we are young, because our bodies are growing. When we are adults and no longer growing, our cells don't divide as much. But when our cells die or become damaged, they can usually replace themselves. An example of this is when we cut our skin. Normal cells send and receive signals to tell one another that there is damage (the cut) and that new cells are needed to repair it. When the cut has healed over, the cells signal to one another to stop dividing.

G1 phase– The cell starts to grow in size. Once it has gotten bigger, the cell gets a signal to divide or not divide. If the cell gets a signal to not divide, it enters G0. If the cell gets a signal to divide, it enters S phase.

G0 phase – The cell is not growing or dividing. But it is still working to support body tissues and produce energy for the body. Some cells will move back to the G1 phase when they get the signal that new cells are needed. Other cells will stay in G0 permanently.

S (synthesis) phase–

Proteins inside the cell copy its

G2 phase– The cell continues to grow and get ready to divide. Proteins found in the cells check that all of the DNA has been copied correctly.

M phase –

This is when the cell divides. This phase is made up of mitosis (division of

the

There are now 2 identical and fully functional cells, each with 1 copy of DNA. Once the cell has divided, both cells enter G1 to begin the cycle again.

Cancer cells are different from normal cells. They don't grow or divide normally. Find out more about how cancer starts, grows and spreads.

Chemotherapy drugs

Having chemotherapy

Taking oral chemotherapy at home

Side effects of chemotherapy

Sources of drug information

Your trusted source for accurate cancer information

With support from readers like you, we can continue to provide the highest quality cancer information for over 100 types of cancer.

We’re here to ensure easy access to accurate cancer information for you and the millions of people who visit this website every year. But we can’t do it alone.

Every donation helps fund reliable cancer information, compassionate support services and the most promising research. Please give today because every contribution counts. Thank you.