Male reproductive system problems

Reproductive system problems can develop after some types of cancer treatment. Sometimes they happen as a late effect of treatments for cancer during childhood.

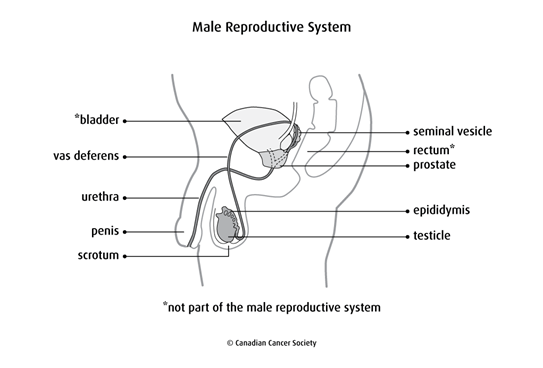

The male reproductive system

The testicles are made up of cells that make testosterone and cells that make sperm. A sperm needs to fertilize an egg for pregnancy to happen.

The male reproductive system is controlled by the pituitary gland in the brain. When puberty begins, the pituitary gland signals the testicles by releasing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). The testicles then start to make testosterone and sperm. Testosterone is responsible for male sexual development, including deepening of the voice, enlargement of the penis and testicles, growth of facial and body hair and muscle development.

Types of male reproductive system problems

Reproductive problems that can develop after treatment for cancer include:

Early, delayed or absent puberty

Puberty usually happens when a boy is 9 to 13 years of age. The first signs of puberty are usually enlargement of the testicles and hair growth under the arms and in the pubic area.

Some cancer treatments can affect when puberty starts. It can start earlier (called precocious puberty) or later (called delayed puberty) than normal. Sometimes puberty doesn’t start at all, which is called absent puberty.

Infertility

Infertility is the inability to get someone pregnant. It can happen when cancer treatments cause a low sperm count. Infertility after treatment for cancer can be temporary or permanent.

Lack of testosterone

Lack of testosterone (testosterone deficiency) is also known as hypogonadism. It happens when the testicles don’t make enough testosterone.

Causes

Treatments for cancer, including some types of chemotherapy, radiation therapy and surgery, can cause male reproductive system damage.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy with certain drugs, particularly alkylating drugs, can affect the testicles. Damage to the testicles can lead to infertility or testosterone deficiency.

Damage to the reproductive organs is often related to the type and dose of chemotherapy drugs given and the length of treatment. The higher the total dose of chemotherapy, the greater the risk that the testicles will be damaged.

Chemotherapy used in combination with radiation therapy also increases the risk of damage to the testicles.

High doses of chemotherapy used in preparation for a stem cell transplant can cause testosterone deficiency and infertility.

Chemotherapy drugs that can increase the risk of male reproductive problems include:

- busulfan (Busulfex)

- chlorambucil (Leukeran)

- cisplatin

- cyclophosphamide (Procytox)

- mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard, Mustargen)

- procarbazine hydrochloride (Matulane)

- lomustine (CeeNU, CCNU)

- carmustine (BiCNU, BCNU)

- melphalan (Alkeran)

- doxorubicin (Adriamycin)

Radiation therapy

The total dose of radiation, area of the body being treated and age at the time of treatment can increase the risk of damage to the reproductive system.

Men over the age of 40 are more likely to have permanent damage to the reproductive system. But higher doses of radiation can cause the testicles to stop working at any age.

Radiation therapy to the testicles, pelvis, lower back, abdomen or total body (called total body irradiation, or TBI) can cause reduced testosterone production, infertility or reduced fertility. This can happen because Leydig cells in the testicles, which make testosterone, can be damaged by radiation.

Radiation can also damage germ cells in the testicles, which make sperm. This damage leads to lower numbers of sperm. Low sperm count and infertility may be temporary or permanent. Sperm count can return to normal later, sometimes up to 15 years after having radiation therapy.

Radiation therapy to the brain can damage the pituitary gland. This results in lower levels of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone. Low levels of these hormones mean the testicles make fewer sperm and less testosterone.

Surgery

Surgery for cancers of the reproductive system and for other cancers in the pelvis can cause reproductive problems or affect sexual function.

- Surgery to remove both testicles will cause infertility.

- Removal of tumours in the pelvis, including in the bladder, colon and rectum, can damage the reproductive organs or nearby nerves and cause impotence.

- Surgery to remove the prostate gland can affect sexual function.

- Surgery on the spine or the removal of a tumour near the spinal cord can damage nearby nerves and affect sexual function.

Other factors

Other factors, such as hormonal therapy and some types of targeted and immunotherapy drugs, may increase the risk of reproductive problems by causing damage to the testicles.

Symptoms

Sometimes cancer treatment damages the testicles so they can’t make hormones and produce sperm.

Signs and symptoms of male reproductive system damage include the following fertility issues and testosterone and puberty issues.

Fertility issues include:

- a lower number or poorer quality of sperm

- lowered libido (sexual desire)

- impotence (being unable to get or keep an erection)

Men with infertility may notice that their testicles are smaller or less firm, but other men may have no physical signs of infertility. A man may have sexual function but be infertile.

Testosterone and puberty issues include:

- puberty that starts late or doesn’t start at all

- lack of secondary sex characteristics, including deepening voice, enlargement of the penis and testicles, growth of facial and body hair and muscle development

If symptoms get worse or don’t go away, report them to your doctor or healthcare team without waiting for your next scheduled appointment.

Diagnosis

Your doctor will try to find the cause of your reproductive system problems. You will be asked questions about your symptoms and may have a physical exam. When young boys are treated for cancer, the healthcare team will watch for signs of reproductive problems. They will pay attention to when puberty starts and how it progresses.

You may have blood tests to check the levels of follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone and testosterone. Sperm may be collected to do a sperm count and analysis.

Preventing reproductive system problems

Before a boy or man starts cancer treatments, fertility counselling may be offered. The fertility counsellor or healthcare team will discuss possible side effects of treatments that may affect fertility in the future.

Radiation shielding is usually done when radiation is given to the abdomen or pelvis, unless the shielding will increase the chance that the cancer will come back. Shields are placed over one or both testicles. In some cases, the testicles may be moved out of the treatment field to help protect them from damage during radiation therapy.

Sperm banking is a way to preserve fertility in young men who have gone through puberty before treatment. Semen samples can be collected as often as every day before starting cancer treatment. They are stored for future use in artificial insemination or in vitro fertilization.

Testicular sperm extraction (TESE) is a way to collect sperm for men who are unable to produce a semen sample. The sperm is frozen for use in the future.

Freezing testicular tissue may be an option for boys who have not gone through puberty and are at high risk of infertility. It is still considered experimental in many hospitals.

Managing reproductive system problems

If the healthcare team finds any reproductive system problems after treatment for cancer, you may be referred to one or more of the following specialists:

- an endocrinologist (hormone specialist)

- a urologist (specialist in the male reproductive organs)

- a fertility specialist

The healthcare team can suggest ways to manage the following reproductive system problems.

Lack of testosterone

If lack of testosterone (testosterone deficiency) happens before a boy goes through puberty, he will need to take testosterone therapy to start puberty. He will also need testosterone therapy if the deficiency happens after puberty. Testosterone may be given in the form of injections, patches or gels applied to the skin. The testosterone helps maintain muscular development, bone and muscle strength, proper distribution of body fat, sex drive and the ability to have erections.

Infertility

If infertility is permanent, donor sperm can be used to produce a pregnancy.

Life after treatment

Some studies have shown that cancer survivors may think that they can’t get someone pregnant. Because of this belief, they might not use birth control and then have an unplanned pregnancy. Talk to your doctor about your fertility and if you need to use birth control.

Talk to your doctor if you and your partner are considering pregnancy after cancer treatments are over. Your doctor may recommend that you wait at least 6 months or more after cancer treatment before trying to conceive. Some doctors may suggest delaying pregnancy for about 2 years after treatment. How long you have to wait depends on many factors, including:

- the type and stage of your cancer

- your prognosis

- your age

- what you prefer or want

Find out more about fertility problems.

Follow-up

All men who are treated for cancer need regular follow-up. The healthcare team will develop a follow-up plan based on the type of cancer, how it was treated and your needs.

Make sure you tell your doctor all the treatments you received. Men who are at risk for reproductive system problems should have a physical exam each year.

During follow-up, your doctor may:

- ask questions about your sexual development and if you’ve had any sexual problems

- do blood tests for levels of follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone and testosterone

- do semen analysis

Your trusted source for accurate cancer information

With support from readers like you, we can continue to provide the highest quality cancer information for over 100 types of cancer.

We’re here to ensure easy access to accurate cancer information for you and the millions of people who visit this website every year. But we can’t do it alone.

Every donation helps fund reliable cancer information, compassionate support services and the most promising research. Please give today because every contribution counts. Thank you.