What is ovarian cancer?

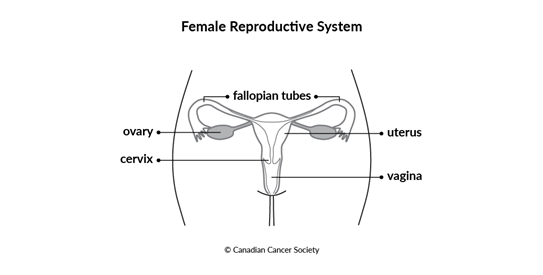

The ovaries and fallopian tubes are part of the female reproductive system. The ovaries produce eggs and make sex hormones in pre-menopausal women. During the menstrual cycle, an egg travels through a fallopian tube from the ovary to the inside of the uterus.

There are 2 ovaries. Each one is located deep in the pelvis on either side of the uterus (womb), close to a fallopian tube. There are 2 fallopian tubes on either side of the uterus.

Cells in an ovary or fallopian tube sometimes change and no longer grow or behave normally. Changes to ovarian cells may lead to non-cancerous (benign) conditions such as cysts. They can also lead to non-cancerous tumours, such as benign epithelial ovarian tumours.

Changes to cells in a fallopian tube can cause a precancerous lesion called serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC). Precancerous means that the abnormal cells are not yet cancer, but there is a chance that they will become cancer if they aren't treated.

In some cases, changes to cells of an ovary or fallopian tube can cause cancer. A

cancerous (malignant) tumour is a group of cancer cells that can grow into nearby

tissue and destroy it. The cancer cells can also spread (metastasize) to other parts

of the body. Most ovarian cancers start in the epithelial cells. These cells are

found in the tissue that covers each ovary and lines the fallopian tubes and

It's often hard to know if cancer started in the ovaries. Most epithelial ovarian cancers are now thought to start in the nearby fallopian tube, but it’s very difficult to find cancer there.

Fallopian tube cancer and primary peritoneal cancer are very similar to epithelial ovarian cancer. They start in epithelial tissue, cause the same symptoms, and are staged and treated the same way. But they are much less common than ovarian cancer.

Other than epithelial ovarian cancer, rare types of ovarian cancer can also develop. These include germ cell ovarian cancer and stromal cell ovarian cancer.

The ovaries and fallopian tubes

The ovaries are the organs in a woman’s reproductive system that produce eggs (ova). There are 2 of them, and they are deep in a woman’s pelvis, on both sides of the uterus (womb), close to the ends of the fallopian tubes.

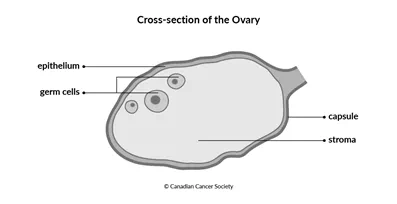

Structure

Different types of cells and tissue are found in the ovaries.

The epithelium is the tissue that covers the ovary. It also lines the fallopian tubes and

Germ cells are inside the ovary. They develop into eggs.

The stroma is the supportive or connective tissue of the ovary. It is made up of stromal cells.

The capsule is a thin layer of tissue that surrounds each ovary.

What the ovaries and fallopian tubes do

The ovaries have 2 main functions. They make the sex hormones estrogen and progesterone. They also produce eggs.

During ovulation each month, an ovary releases an egg. The fallopian tubes carry the egg from the ovary to the inside of the uterus. If the egg is fertilized by a sperm, the egg attaches itself to the lining of the uterus (called implantation) and begins to develop into a fetus. If the egg is not fertilized, it's shed from the body along with the lining of the uterus during menstruation.

During menopause, the ovaries stop making sex hormones and releasing eggs.

Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC)

Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) is a precancerous lesion that can develop in a fallopian tube. This means that there are changes to cells of the fallopian tube that make them more likely to develop into cancer. STIC is not yet cancer. But if it isn’t treated, there is a chance it will become cancer.

STIC is rare, but can spread to the ovaries and become a cancerous tumour called high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC). It can also spread to the peritoneum and develop into primary peritoneal cancer.

Risks

The following risks increase your chance of developing STIC:

- BRCA gene mutations

- a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancers

Symptoms

There are typically no signs or symptoms of STIC.

Diagnosis

STIC is often found during surgery to remove the ovaries and fallopian tubes (called a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) or surgery to cut or block the fallopian tubes (called a tubal ligation or getting your tubes tied). These surgeries prevent pregnancy. They may also be done to prevent or treat ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer.

If the surgeon sees abnormal cells they think might be STIC, they will remove different samples of tissue. STIC is diagnosed after the samples are tested in the lab.

Treatments

STIC can be treated before it becomes cancer. Surgery can be used to completely remove the precancerous cells.

Borderline ovarian tumours

A borderline ovarian tumour is a group of abnormal cells in the tissue covering the ovary. Cancer cells typically grow and divide out of control. Doctors may not classify borderline ovarian tumours as cancer because they grow slower and in a more controlled way than cancer cells. They also don’t grow into (invade) nearby tissue like ovarian cancer does. These tumours are also called tumours of low malignant potential.

Borderline ovarian tumours usually develop between the ages of 20 and 40 years old. Since they grow very slowly, most are stage 1 when they are diagnosed. They are most commonly found in 1 or both ovaries but can, in rare cases, start in the fallopian tube or peritoneum.

There are different types of borderline ovarian tumours. The most common types are the following.

Serous borderline tumours can turn into a cancerous ovarian tumour called low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC).

Mucinous borderline tumours sometimes come back (recur) after treatment as mucinous carcinoma.

Less common borderline ovarian tumours typically develop in only 1 ovary and include:

- endometrioid tumours

- Brenner tumours

- clear cell borderline ovarian tumours

Cancerous tumours of the ovary

Non-cancerous tumours and conditions of the ovary

Your trusted source for accurate cancer information

With just $5 from readers like you, we can continue to provide the highest quality cancer information for over 100 types of cancer.

We’re here to ensure easy access to accurate cancer information for you and the millions of people who visit this website every year. But we can’t do it alone.

If everyone reading this gave just $5, we could achieve our goal this month to fund reliable cancer information, compassionate support services and the most promising research. Please give today because every contribution counts. Thank you.