Surgery for eye cancer

Surgery is a medical procedure to examine, remove or repair tissue. Surgery, as a treatment for cancer, means removing the tumour or cancerous tissue from your body. This usually means cutting into the body. But surgery to remove cancer can also be done in different ways, such as using heat, cold or lasers.

Surgery is sometimes used to treat eye cancer. The type of surgery you have depends mainly on the type of eye cancer you have, the size of the tumour and where the tumour is in the eye. When planning surgery, your healthcare team will also consider other factors, such as whether the cancer has spread and how surgery will affect your vision.

Surgery may be the only treatment you have or it may be used along with other cancer treatments. You may have surgery to:

- completely remove the tumour

- remove as much of the tumour as possible (called debulking) before other treatments

- reduce pain or ease symptoms (called palliative surgery)

- treat cancer that comes back (recurs) after other treatments (called salvage surgery)

If

Surgery for eye cancer is usually done by an ocular oncologist (a medical doctor who specializes in treating eye cancers). They will talk to you about what to expect from the surgery and explain how it will affect your vision and your appearance (how you look).

The following types of surgery are used to treat eye cancer.

Surgical excision

Surgical excision removes the tumour along with some normal tissue around it (called the surgical margin). Other names for surgical excision include surgical resection or local excision. It's sometimes called eye-sparing surgery because it doesn’t remove the eyeball.

Surgical excision for eye cancer is usually done with a

Small tumours in the eye may be treated with surgical excision. It is most commonly used for:

- squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- melanoma of the conjunctiva

- uveal melanoma in the ciliary body

If you have surgical excision, you will usually have radiation therapy afterward.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery destroys cancer cells by freezing them. Doctors apply an extremely cold liquid or gas to the eye or surrounding tissues through a metal tube called a cryoprobe. The area is allowed to thaw and then is frozen again. The freeze-thaw cycle may need to be repeated a few times.

Cryosurgery is sometimes used to treat eye cancer. It's usually used after another treatment. You may have cryosurgery:

- after radiation therapy for uveal melanoma

- after surgical excision of conjunctival tumours, including SCC and melanoma

- after an enucleation or orbital exenteration if cancer spreads to the eye socket

- for eye cancer that has come back (recurred) and spread outside the eye

Learn more about cryosurgery.

Laser surgery

Laser surgery uses a powerful, narrow beam of light (called a laser beam) to destroy cancer cells. It's also called laser therapy.

Some people with eye cancer will have laser surgery. You may have laser surgery to:

- kill cancer cells in the eye

- destroy cancer cells left behind after radiation therapy and reduce the risk that the cancer will come back (recur) (called adjuvant therapy)

- treat eye cancer that comes back after treatment

Transpupillary thermotherapy (TTT) is a type of laser surgery that uses an infrared laser to heat and kill cancer cells. It's sometimes called diode laser hyperthermia. TTT can be used to treat small tumours in the uvea, choroid or retina. Before starting TTT, the doctor uses eye drops to make the pupils larger (dilate the pupils). This allows the beam of light from the laser to pass through the pupil and into your eye.

Find out more about laser surgery.

Enucleation

An enucleation removes the eyeball and part of the optic nerve. The eyelids, muscles, nerves, fat and bone of the eye socket (orbit) are left in place.

This surgery is not used to treat eye cancer as often as it was in the past. Radiation therapy, specifically brachytherapy, is often now preferred because it allows you to keep your eye and usually some or all of your vision.

Your healthcare team may recommend an enucleation for:

- large or advanced tumours

- tumours that cause pain or high pressure inside the eye (glaucoma)

- cancer that has spread to the sclera or optic nerve

- cancer that has come back (recurred) after other treatments

- smaller tumours when vision has already been lost in the affected eye or other treatments would result in vision loss as well

In some cases, other treatments such as radiation therapy can cause side effects (for example, glaucoma) that mean you need to have an enucleation.

After an enucleation, you may have challenges with depth perception and vision at first. Over time, most people adapt to having vision in only 1 eye.

Enucleation surgery is done under a

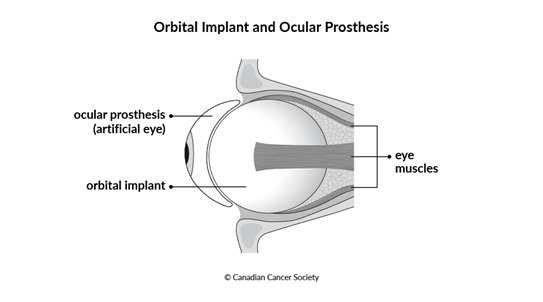

Orbital implant and ocular prosthesis

An orbital implant and an ocular prosthesis are medical devices that replace an eyeball that has been removed. They can’t restore vision, but they can help you feel more confident in your appearance (how you look).

An

orbital implant

is a sphere made of plastic, metal, glass or a material similar to bone that

is placed in the eye socket to help maintain the shape after the eyeball is

removed. It's attached to the muscles that control the eyeball so it can

move around in the same way the eyeball did. A conformer (a plastic,

disk-shaped

Some types of implants can later have a hole drilled into them to insert a peg (this creates a pegged implant). The peg helps to better hold the prosthesis in place and increase movement of the artificial eye. Surgery to insert the peg is usually done 6 to 12 months after enucleation.

Side effects of pegged implants include an increased risk of infection and extrusion (when the body pushes the implant out of the socket). Because of these side effects, pegged implants are not as common as they used to be.

An ocular prosthesis (sometimes called an artificial or “glass” eye) is like a large contact lens that is placed behind the eyelids in front of the orbital implant. It’s made of plastic or glass that is painted to look like a real eyeball. The orbital implant helps to hold the prosthesis in place.

After an enucleation, you need to heal before you can be fitted for an ocular prosthesis. About 4 to 8 weeks after surgery, you will see an ocularist (a healthcare professional who specializes in making ocular prostheses). They will make the prosthesis to fit your eye socket and paint it to match the other eye as closely as possible. The ocularist will teach you how to put in, remove and take care of your prosthesis. While your prosthesis is being made, you may be given a temporary prosthesis or an eye patch.

Orbital exenteration

An orbital exenteration (sometimes called just exenteration) removes the entire eye including the eyeball and surrounding tissues and structures. This can include the eyelids, muscles, nerves, fat and bone of the eye socket (orbit). How much is removed with the eyeball depends on what parts of the eye are affected by cancer.

Having an orbital exenteration is very rare. It's typically only used to treat eye cancer that has spread to the orbit or for tumours that are causing pain that will not be solved by an enucleation.

When you have an exenteration, you may have challenges with depth perception and vision at first. Over time, most people adapt to having vision in only 1 eye.

An orbital exenteration is done under general anesthesia. Your ophthalmologist will talk to you about how to prepare and what the recovery process is like. Exenteration changes how you look and leaves a bowl-shaped cavity in the face where the eye used to be. You may choose to wear an eye patch or a facial prosthesis called an orbital prosthesis after exenteration surgery.

An orbital prosthesis is a device made to look like an eye and the surrounding structures of the face. It's made just for you and painted to look as realistic as possible. It may be held in place by pegs that are implanted into the remaining bone surrounding the eye. It can’t restore vision, but it can help you feel more confident in your appearance.

Reconstructive surgery

Surgery for eye cancer sometimes damages or removes large portions of the tissue around the eye. This can affect the way you look.

In some cases, reconstructive surgery can repair damage, rebuild structures or make you feel more confident in your appearance. It usually involves removing tissue (such as skin, muscle and bone) from another part of the body to use in the reconstruction. Sometimes, donated tissue may be used when parts of the sclera or cornea need to be reconstructed.

When planning reconstructive surgery, your healthcare team will consider factors such as what you want, the recovery process and if your treatment plan includes other treatments. Most of the time, reconstructive surgery for eye cancer is done as a separate procedure after surgery to remove the cancer.

Surgery to prepare for radiation therapy

Some types of radiation therapy for eye cancer involve placing a device on the eye. Surgery is used to attach or remove the device.

For brachytherapy (plaque therapy), surgery is used to place a plaque (a container shaped like a bottle cap that contains small radioactive particles). The plaque is placed on the surface of the eye over the tumour and stitched into the sclera. It's left in place for a few days and then another surgery is done to remove it. You will have to stay in the hospital while the plaque is on your eye.

For proton therapy, surgery is needed to place metal clips (called tags or tantalum markers) on the outside of the eye around the tumour. They help to direct the beam of protons to the tumour. The clips are stitched into the sclera to keep them in place.

You can have local or general anesthesia before having surgery to place a plaque or clips.

Side effects of surgery

Side effects of surgery will depend mainly on the type and site of surgery and your overall health. Tell your healthcare team if you have side effects that you think are from surgery. The sooner you tell them of any problems, the sooner they can suggest ways to help you deal with them.

Surgery for eye cancer may cause these side effects:

- pain in the eye

- swelling and bruising around the eye

- dry eyes

- headaches

- eyelids or muscles around the eye drooping

- bleeding or a blood clot

- vision changes, including light sensitivity and loss of vision

- loss of eyelashes

- infection

-

cataracts - separation of the layers of the retina (detached retina)

- orbital implant moving out of place

-

a

fistula between the eye socket and the hollow parts inside the nose (the nasal cavity)

Find out more about surgery

Find out more about surgery and side effects of surgery. To make the decisions that are right for you, ask your healthcare team questions about surgery.

Your trusted source for accurate cancer information

With support from readers like you, we can continue to provide the highest quality cancer information for over 100 types of cancer.

We’re here to ensure easy access to accurate cancer information for you and the millions of people who visit this website every year. But we can’t do it alone.

Every donation helps fund reliable cancer information, compassionate support services and the most promising research. Please give today because every contribution counts. Thank you.