Lung problems

Lung problems can develop after some types of cancer treatment. Lung problems usually develop many years after treatment is finished. Sometimes lung problems happen as a late effect of treatments for cancer during childhood. Lung problems often develop slowly and progress gradually over time.

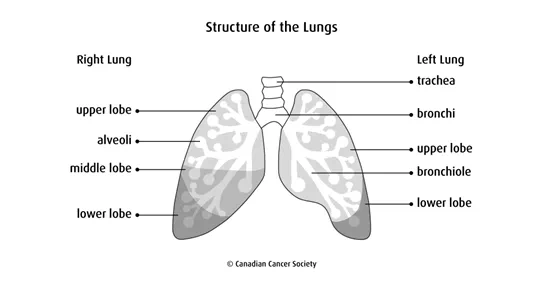

How the lungs work

The lungs are part of the respiratory system. There are 2 lungs, one on each side of the chest. Each lung has tubes, called bronchi, which branch out into smaller and smaller tubes. These tubes eventually branch out into very small tubes called bronchioles. At the end of the bronchioles are millions of tiny sacs called alveoli.

Air enters the mouth or nose and travels through the trachea (windpipe), bronchi and bronchioles to the alveoli. The alveoli absorb oxygen from the air and pass it to the blood, where it is circulated throughout the body. Carbon dioxide, a waste product made by cells, passes from the blood into the alveoli and is breathed out of the body.

Causes

Treatments for cancer, including some types of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, can cause lung problems. The risk of developing lung problems is greater if both chemotherapy and radiation therapy were used to treat the cancer. Lung damage is often related to the dose of the drugs or radiation used. The higher the dose, the greater the risk for lung damage.

Chemotherapy

Some chemotherapy drugs known to cause lung damage are:

- bleomycin (Blenoxane)

- carmustine (BiCNU, BCNU)

- lomustine (CeeNU, CCNU)

- busulfan (Busulfex)

Some chemotherapy drugs that can damage the heart can also contribute to lung problems, especially if they are given in combination with a drug that is known to cause lung damage or with radiation therapy. These drugs include:

- daunorubicin (Cerubidine, daunomycin)

- doxorubicin (Adriamycin)

- idarubicin (Idamycin)

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy to the chest, abdomen or spine can lead to lung problems.

Surgery

Previous surgery to your chest or lungs can increase the risk of lung problems.

Stem cell transplant

High-dose chemotherapy and total body irradiation (TBI) given before a stem cell transplant increases the risk of lung problems. The risk of lung problems also increases if graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) develops after an allogeneic stem cell transplant.

Other factors

Other factors can also increase the risk of developing lung problems.

- The young and the elderly are at a greater risk for developing lung problems, with those at a younger age at the time of treatment having the greatest risk.

- A history of lung diseases such as infections or asthma increases the risk of lung problems after cancer treatment.

- Your risk of lung problems is increased if you use tobacco or are exposed to second-hand smoke.

Types of lung problems

Types of lung problems that can develop following some types of cancer treatment include:

Pulmonary fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis is the formation of scar tissue in the tiny air sacs in the lungs (called alveoli). Scarring makes the lungs stiffer and affects the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Inflammation and infection

Lung problems or damage can result in lung inflammation and infection that keep happening and may become chronic.

- Bronchitis is inflammation of the mucous membranes that line the bronchi and often improves with no long-term damage.

- Bronchiectasis is permanent damage and widening of the large airways in the lungs with a buildup of extra mucus, which leads to frequent lung infections.

- Pneumonia is infection of one or both lungs caused by bacteria, viruses or fungi and often improves with no long-term damage.

Pneumonitis

Pneumonitis is inflammation of the thin layer of tissue between the tiny air sacs in the lungs (called alveoli). The main concern about pneumonitis is that it can progress to permanent pulmonary fibrosis.

Radiation pneumonitis is caused by radiation therapy. It can develop up to 6 months after treatment.

Some chemotherapy drugs such as docetaxel (Taxotere) can also cause pneumonitis. It can also develop if you are exposed to toxic fumes, tobacco or high levels of oxygen over several hours.

Restrictive or obstructive lung disease

Lung damage can cause the tiny air sacs in the lungs to break. It can also cause airways in the lungs to thicken or become blocked. These problems can cause restrictive or obstructive lung disease.

Obstructive lung disease is when you can’t exhale all the air from your lungs. Restrictive lung disease is when you can’t fully expand your lungs when you inhale. Both make it hard to breathe and cause shortness of breath.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a serious condition that occurs when the tiny air sacs in the lungs are damaged and no longer provide oxygen to the body. People who receive bleomycin (Blenoxane) may be at slightly higher risk of developing ARDS later in life. ARDS usually develops if you also received high levels of oxygen and large amounts of intravenous fluid during surgery.

Symptoms

Symptoms of lung problems can vary depending on the type of problem. Symptoms include:

- coughing

- fever

- shortness of breath

- wheezing

- chest pain

- frequent lung infections, such as bronchitis or pneumonia

- fatigue or shortness of breath during exercise

If symptoms get worse or don’t go away, report them to your doctor or healthcare team without waiting for your next scheduled appointment.

Diagnosis

Before treatment for cancer begins, the healthcare team may do tests to check lung function and make sure there are no major problems. Tests may also be done during and after treatments to make sure nothing has changed.

Your doctor will try to find the cause of the lung problem. Tests may include:

- a physical exam, including listening to the lungs

- a chest x-ray or CT scan to look for abnormalities or disease in the lungs

- blood tests to check the level of oxygen in the blood

- a pulmonary function test to measure lung function

- a bronchoscopy to look at the windpipe and large airways of the lungs

Find out more about tests and procedures.

Preventing lung problems

To prevent lung damage, the healthcare team carefully monitors people who are receiving cancer treatments that can affect the lungs. If they think the lungs might be damaged, they may lower the dose of the drug or radiation or stop the treatment entirely to prevent further damage.

If your cancer treatment has increased your risk of lung problems, you can help lower your risk by:

- not smoking and avoiding second-hand smoke

- getting the pneumococcal (pneumonia) vaccine

- getting yearly influenza (flu) vaccines

- exercising regularly

- avoiding strong fumes from toxic chemicals, paints and solvents

- following all safety rules in the workplace, especially using protective ventilators

- not scuba diving unless a lung specialist says that diving is safe for you (underwater pressure and high oxygen levels can damage the lungs)

Managing lung problems

If your lungs are damaged after cancer treatment, your healthcare team will develop a plan to help manage lung problems. They may suggest the following to relieve symptoms of lung problems:

- corticosteroids

- bronchodilators

- expectorants

- antibiotics

- oxygen therapy

If you have shortness of breath the following may help:

- not smoking and avoiding second-hand smoke

- planning activities with rest periods or deciding which activities are the most important

- using techniques to slow and improve breathing

Find out more about difficulty breathing.

Follow-up

All people who are treated for cancer need regular follow-up. The healthcare team will develop a follow-up plan based on the type of cancer, how it was treated and your needs.

Make sure you tell your doctor all the treatments you received. If you are at risk for lung problems, you should have a physical exam each year.

Follow-up may include one or more of the following tests:

- a chest x-ray

- a blood test that measures the amount of oxygen in the red blood cells (oxygen saturation test)

- pulmonary function tests

Your trusted source for accurate cancer information

With support from readers like you, we can continue to provide the highest quality cancer information for over 100 types of cancer.

We’re here to ensure easy access to accurate cancer information for you and the millions of people who visit this website every year. But we can’t do it alone.

Every donation helps fund reliable cancer information, compassionate support services and the most promising research. Please give today because every contribution counts. Thank you.